TIL-1: Move Semantics, Exception and Smart Pointers

Table of Contents

CPPCON 2019: Move Semantics - Klaus⌗

std::move and rvalue reference are ways to tell compilers to “move” the content from one to the other

- Note: the reason that

T&&is a lvalue is because even though caller explicitly moves some content into a function, for example, the designer of the function can still do many stuff inside this function. Therefore, they should ensure they std::move the rvalue reference again to trigger move constructor/assignment

- Note: the reason that

std::move unconditionally casts

Tinto a rvalue reference// possible implementation of std::move template<typename T> std::remove_reference_t<T>&& move(T&& t) noexcept { return static_cast<std::remove_reference_t<T>&&>(t); }Default Move and Copy

- The default move operations (move constructors/assignments) are generated if no copy operation or destructor is user-declared

- Note: Klaus uses “user-defined” instead of “user-declared”. However, in cppreference, it uses the word “user-declared”.

- The default copy operations are generated if no move operation is user-declared

- They “prefer” copy operations

- Note:

=defaultand=deletecount as user-declared!

- The default move operations (move constructors/assignments) are generated if no copy operation or destructor is user-declared

The default behavior of move/copy leads to the rule of 0 or rule of 5

- Either you define nothing (only constructors) or You define everything (destructors, copy constructors, copy assignment, move constructors, move assignment)

- You don’t want your user to memorize these default behaviors

Forwarding References (Universal References)

- Used in std::move implementation

- Forwarding References in this exact form:

T &&. Evenconst T&&is not considered as universal reference - How can we create a function that takes in anything (lvalue, rvalue), and forward them as their original type?

The problem arises because the rvalue reference is lvalue

std:: forward conditionally casts its input into an rvalue reference: it takes in an lvalue and forward them based on their original type

How it works

- The

Tin universal reference is deduced asT&if lvalue andTis rvalue - We call

std::forward<T>(arg)as this, so after castingT&isT&andTisT&&, which is what we expect

template<typename T> T&& forward(std::remove_reference_t<T> &t){ return static_cast<T&&>(t); }- The

CPPCON 2019: Exception Handling - Ben⌗

Talk: Back to Basics: Exception Handling and Exception Safety

Ideas behind Exception Handling: separate the error reporter from error handler

Traditional C-style error handling

- check return value

- check

errno - Drawbacks: if the caller cannot handle this, they need to propagate the error code back in their return value, which somewhat interferes with the normal return path (my point)

C++ EH separates this from the normal control flow by providing an exceptional control flow with

- throw

- try

- catch

- Idiomatic way to catch exception:

catch(T &arg){}. Use a reference of type T here.

- Idiomatic way to catch exception:

Exception hierarchy

- In

<exception>, the base exception is defined, which specifies the base class used by all exceptions in STL - In

<stdexcept>, common exceptions likestd::out_of_rangeandstd::runtime_errorare defined

- In

Behaviors

- Once a function is throw-ed, we try to find a function in previous stack frame that can handle the exception

- If no such function exists and we are out of main,

std::terminateis called - If before catching the exception, we encounter another exception (e.g. some destructors throw during stack unwinding),

std::terminateis called. - Failure in Constructors

- If an exception is thrown in constructor, it’s like the object doesn’t exists

- So, you need to release any resources that are allocated before this exception happens

- RAII can help now

Exception Safety

- Basic

- Function may throw an exception

- Program’s state may change, but it’s still in consistent state (no memory leak, no invalid state)

- Strong

- Program’s state remains unchanged

- To achieve strong guarantee, we could

- First, do everything that could throw and store their result in local variable

- Update the state of the program, using operations that will not throw

- No Throw

noexcept- This is not enforced at compile time but compiler does optimization based on this (see “The cost of Exception” below) and some STL actually relies on this

- If your move constructor/assignment is not defined with

noexcept, containers like vector prefers the copy constructors/assignment as they want a strong exception guarantee (they want the original data be consistent when they try to realloc their spaces)

- If your move constructor/assignment is not defined with

- If a function with

noexceptthrows,std::terminateis called - Some functions should never throw

- destructors

- operator delete

- swap (+ move)

- Operations on primitive types (my point)

- Basic

The cost of Exception (My Point)

- It should only be thrown if the condition is exceptional (because it has a cost related to it)

- Cost of

tryandcatch- When you have

tryandcatch, compilers will leave a path that calls a function that does stack unwinding for you- The standard doesn’t mandate when stack unwinding happens, they usually happen when the function that could handler the exception is found

- If you declare all your functions inside

tryblock withnoexcept, compilers can optimize out this hidden path as it knows now your function will never throw

- When you have

- Cost of

throw- You need to call library function that actually does throw for you

- Then, an iterative process of finding appropriate function that handles your exception occurs

CPPCON 2019: Smart Pointers - Arthur⌗

unique_ptr

- Custom Deleter (a lambda)

- You can use it to manage

fopen/fcloseand generally everything that provides you with a constructor and destructor like stuff (useful when interfacing with system resources) - Need to use traditional functor here or stateless lambdas are default constructible (since C++20)

- You can use it to manage

- Code smell: passing a pointer by reference is usually a code smell

- If you want to denote ownership transfer, pass by value

- Custom Deleter (a lambda)

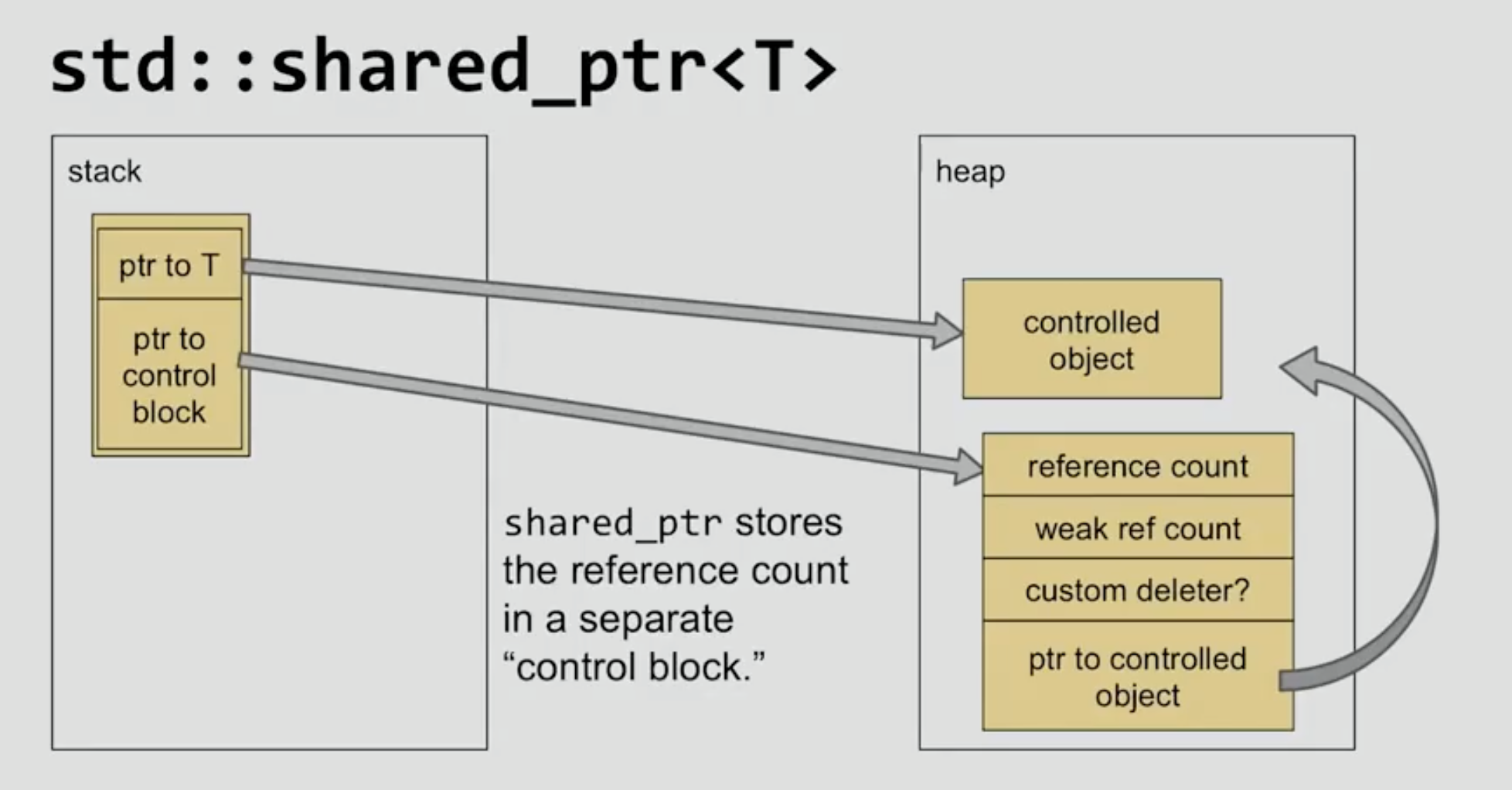

shared_ptr mechanism

- A control block (an atomic reference count, weak ptr count, deleter and actual pointer to the object) + An actual object

- Aliasing constructors

- The “ptr to T” can point to some elements in classes (int in

vector<int>) or point to subclasses. This is whatshared_ptr.get()returns. - They are irrelevant to the actual pointer being destructed. They only contribute the the reference count

- We could declare those shared pointer like this:

std::shared_ptr new_ptr = std::shared_ptr(another_shared_ptr, some_address).another_shared_ptris the one that you share the ownership with (the control block)

- The “ptr to T” can point to some elements in classes (int in

- Potential optimization of make shared (all about locality)

- Fewer call to

new make_sharedcan enable the allocation to allocate the control block near the actual object which is beneficial in terms of locality

- Fewer call to

- A control block (an atomic reference count, weak ptr count, deleter and actual pointer to the object) + An actual object

weak_ptr

- A tickets to get shared_ptr

- If object is deleted, throw an exception (directly constructing a

shared_ptr) or return nullptr (lock)

- If object is deleted, throw an exception (directly constructing a

- Share the control block and Contribute to the weak reference count

- As soon as reference count + week ref count != 0, we will not destroy the control block

- A tickets to get shared_ptr

enable_shared_from_this

- Conspire with std: if initialized by shared_ptr, we initialize the weak_ptr inside

- Useful for async where you give your ownership to someone

What’s Next⌗

- RAII and The rule of 0

- Lambda

- Type erasure